The Climate #8: Playing with fire

Can our forest ecosystems survive a hotter, drier climate?

Can our forest ecosystems survive a hotter, drier climate?

It’s Jarrah honey collection season, just before Christmas, here in the Southwest of Western Australia. My bees have filled their boots on Jarrah (E.marginata) nectar during the first genuinely wet spring in years. The last Jarrah ‘flowering’ two years ago yielded little. Spring was dry and the Jarrah dropped both leaves and millions of unopened buds due to the lack of rainfall.

However, with the first official day of summer seeing temperatures exceeding 40 °C (104 °F) across much of the Southwest, I have been mindful of bushfire risk. I timed my forest honey collection with a cooler break in the weather. Sadly, there has already been one bushfire fighter death recorded here this fire season. Up and down the East Coast of the country at least 40 homes have been destroyed in just the first week of December and another firefighter killed.

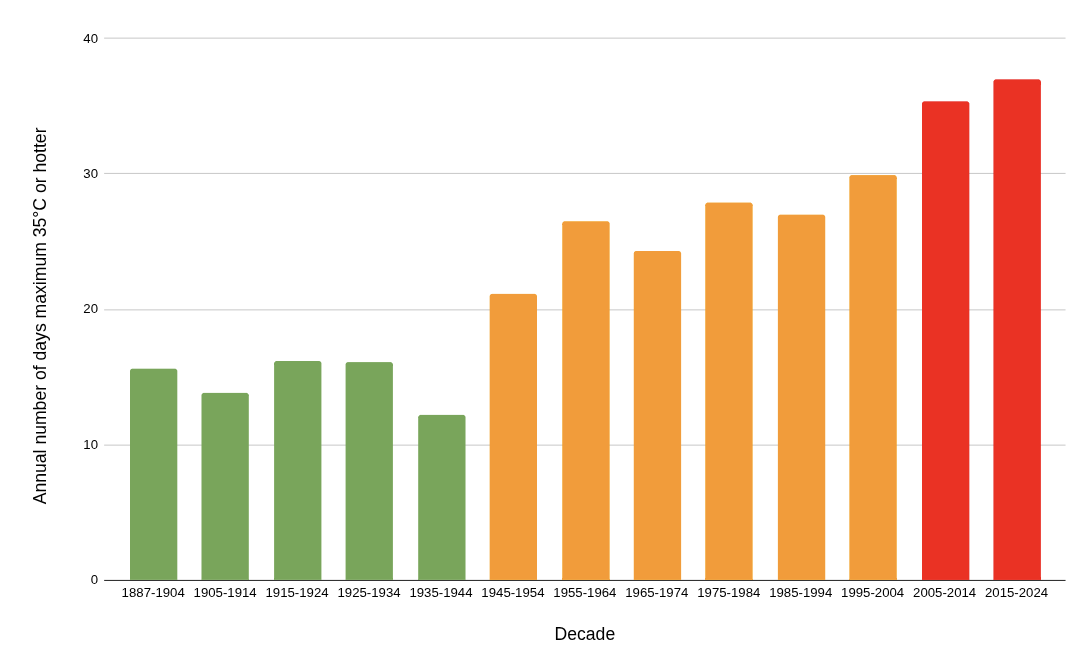

Here in the Southwest, the number of very hot days each year has more than doubled from the pre-WWII baseline and shows no signs of leveling off. This doesn’t bode well for the future of our forests.

Lower winter rainfall, coupled with more hot summer days means greater forest stress, more frequent, hotter bushfires and a rapidly changing forest ecology. This climatic change, which is accompanied by the invasion of post-fire weed species, threatens the survival of much of the unique flora and fauna of this internationally recognised biodiversity hotspot. The Western Ringtail possum (P. occidentalis), once a regular annoyance in the ceilings and walls of Southwest forest huts, is now critically endangered.

Not just ‘our’ forests

These trends in forest stress, catastrophic fires and threats to forest biodiversity are not unique to Australia. Similar trends are seen in many other forested regions worldwide. The European Union recorded its worst ever fire season during 2024 in terms of total area burnt.

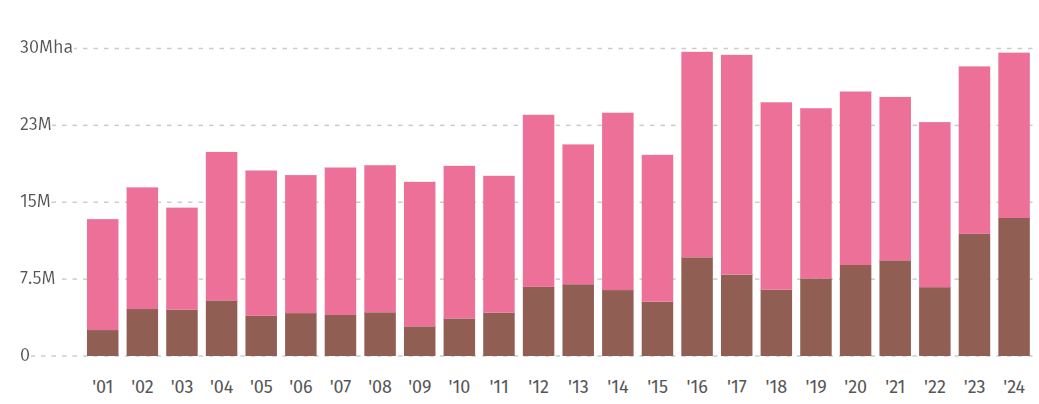

Quoting Global Forest Watch:

‘From 2001 to 2024, there was a total of 150 Mha (ie 150 million hectares) tree cover lost from fires globally and 370 Mha from all other drivers of loss. The year with the most tree cover loss due to fires during this period was 2024 with 13 Mha lost to fires — 45% of all tree cover loss for that year.’

The chart below illustrates a concerning uptrend in global forest loss due to fire. This trend is unlikely to change as global temperatures continue to rise, droughts become more common and fire seasons lengthen. Even if progress is made on other causes of deforestation and fossil fuel burning is curtailed, we risk global forest fires becoming a runaway source of global heating carbon emissions; an emission source that may be difficult to constrain.

From carbon sinks to carbon emitters

Warning signs are flashing red in the Earth’s ‘green lungs’ - the Amazon and Congo Basin tropical rainforests. The combined effects of wild fires and direct deforestation, such as logging, slash and burn farming and cattle ranching, has turned the Amazon into a carbon emitter rather than a carbon sink. And unfortunately, a recent study published in Nature indicates that more persistent and hotter droughts under business as usual carbon-emission scenarios will shift much of the Amazon to a hotter ‘hypertropical’ climate, lethal for large swathes of the forest.

Across the Atlantic, the Congo basin, now acknowledged as the world’s most important terrestrial carbon sink, underpinned by vast peatlands, is also at risk. Mining, illegal logging, agricultural land clearing and increasing fires risks the Congo heading the same way as the Amazon.

Meanwhile, back home, protecting our Australian forests from bushfires, not to mention lives, homes, farms, livestock and wildlife is dangerous and difficult. Measures to reduce bushfire personal and property harm range from clever home design, wide clearances between valuable properties and nearby flammable trees and shrubs and rapid fire detection and suppression measures in bushfire prone areas. Prescribed burning is routinely carried out across large tracts of Australia’s forests; ostensibly aimed at reducing the intensity of bushfires. Done well, in the right places, the right way at the right time of year, prescribed burns can garner approval from all sectors of the community with an interest in fire safety and maintaining forest health and biodiversity.

Not a ‘no-brainer’

Superficially, prescribed burning would seem a ‘no-brainer’. Regular burning, in theory, consumes forest floor fuel loads that could otherwise build up and feed intense, catastrophic fires. However, a ‘one size fits all’ approach can do more harm than good.

As best as forestry services act to manage the risks, prescribed burns can reignite and/or burn out of control if weather conditions unexpectedly change. Burning in hotter months or near areas of forest that tolerate fire poorly (such as near rock outcrops) can do long term ecological damage. All forest fires, including prescribed burns, stimulate rapid, profuse, flammable understorey regrowth. This means that once an area is burnt, it may need to be burnt again and again at short intervals (as little as 2-3 years) to continually suppress the fire risk. Frequent burning changes soil characteristics, not all of which are positive for soil microbial health and forest biodiversity.

In several forest types, particularly old growth forests, it has been shown that leaving the forest unburnt for decades may be more effective at reducing intense fire risk.

Care and respect for our native forests

Here in the Southwest, the recently announced end of commercial native forest logging is welcomed as an important step to reducing bushfire risk. Young regrowth forests following clearfell logging consume large quantities of ground water, leading to drier soils and understory, offer little protection against flame fanning winds and burn more briskly than old growth forest fires.

Ecological thinning, which has already commenced here in WA at a rate of 8000 hectares per annum, has been shown in non-Eucalypt forests of North America and Europe to increase fire resilience as climates become warmer and drier. In Australia, across a range of forest types, thinning young stands of trees planted after clearfelling allows more rapid growth of those that are left, leaves more moisture in the soil to survive droughts, increases understorey diversity and speeds overall forest and habitat maturation. This increases old growth characteristics at an earlier age, such as tree hollow formation. The higher growth rates of thinned tree stands also store carbon more rapidly.

However, on the other side of the ecological coin, thinning can also be aimed at selecting and promoting growth of the best of a young stand of trees for future logging. A change of Government always carries the risk of a change in policy and a resumption of fullscale native forest logging. Community vigilance and preparedness to refight the good fight when needed remain essential. In the meantime, clarity about what and where is being thinned and its ecological benefit is required.

An important win

To end on a positive note, the decision by Alcoa to abandon plans to extend mining exploration in our Southwest forests due to "stakeholder and local community input" is a win for our Southwest forests and water supply. The decision serves as an important reminder to us all to continue our efforts to resist shortsighted corporate and/or government behaviour that acts against the long term interests of ourselves, our forests and the planet we all call home.

We are not the US… yet, but we can learn from resistance movements there (source)

Subscribe to thisnannuplife.net FOR FREE to join the conversation.

Already a member? Just enter your email below to get your log in link.